Seventy-five years ago, U.S. President Harry S. Truman weighed his options — continue to bomb Japan in conjunction with a massive, costly ground invasion, or use a newly developed weapon in hopes it would decisively end the war. It was August 1945, and the president had made up his mind.

On his return from the Potsdam Conference, he addressed the nation aboard the USS Augusta.

“A short time ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima and destroyed its usefulness to the enemy,” reported the president. “ … If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the likes of which has never been seen on this earth … “

Three days later, the Americans dropped an atomic bomb on the coastal city of Nagasaki. On August 14th, 1945, WWII was over. Japan had surrendered.

For descendants of the survivors of Japanese occupied Dutch East Indies like myself, these are not mere factual events. They are decisive historic moments that decided our fate. My six-year-old mother and her five siblings—child prisoners of Japanese internment camps on the island of Java, likely would have not survived much longer. One child, my mom’s seven-year-old brother Menno had already died. Starvation, poor hygiene, brutality and hard physical labour for the older internees, had taken a heavy toll on the thousands of Dutch women and children cramped into Camp Lampersari. Dozens were dying daily.

In 2013, I stumbled across tiny notes in a box recovered from my deceased father’s estate in suburban Toronto, Canada. I was astonished to find the love letters, secretly hand-written by my grandfather — a Dutch missionary and POW assigned to forced labour on the Thai-Burma Railroad. I didn’t even know they still existed. In my hands was a story that had to be told.

Letter writing, I believe, kept my grandfather Menno Giliam’s hope alive. A headmaster of Dutch mission schools, he had been conscripted into the KNIL (Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger) to fight the invading Japanese. Captured in March 1943, “Opa” was separated from his wife and seven children, who unbeknownst to him, were interned by the Japanese on the island of Java. The forbidden, unsent letters document his life as a POW who was eventually transported to Japan and witnessed the devastation of the atomic bomb in Nagasaki first-hand.

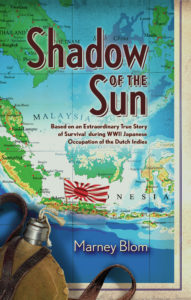

After six years of researching and writing, my family’s story has finally come to life in the book Shadow of the Sun. Its release coincides with commemorations of the 75th anniversary of the end of WWII in the Asia Pacific (August and September 1945).

My grandparents never imagined the cost of answering God’s call to the Dutch East Indies, nor had they envisioned the God-sized answers to simple child-like prayers and the blessings trials would bring. The experience changed their lives for good.

At a time when the world is full of fear and uncertainty, I hope their journey of courage and enduring faith in the face of brutality will raise our spirits and give you hope.

Shadow of the Sun is currently available for pre-order in paperback and eBook formats on www.shadowofthesun.org.